Module 4: Enhancing an Inclusive School Culture for Students with Complex Needs

Including Students with Complex Needs

Here we invite you to look around your own schools and identify words, actions, and physical environments that are preventing an inclusive culture for students with complex needs. Listen to the language that is being used. Observe the physical barriers and watch for behaviours that are examples of an exclusionary setting.

When a student is viewed as a full contributing member of a class it sets the stage for everyone, including the student themselves, to be viewed as a learner. Simple things you might ask yourself could be:

- Is the student enrolled under the classroom teacher, and are they on the class attendance list?

- Is the student attending academic classes, or only elective classes?

- Does the student have a locker or cubby in the same area as their classmates?

- Does the student have their own desk or table space in the classroom?

- If this is what happens for every student, is the student assigned a classroom job and rotating responsibilities?

- Do other students know them and engage with them?

- If there was something more you needed to learn about the student, who would know the answer?

- Is the student included in field trips, and special school-wide events?

- Is the student engaging in their own learning goals while engaging with the learning that’s happening in the class?

"No student is too anything to be able to read and write."

David Yoder, DJI-Ablenet Literacy Lecture, ISAAC 2000

The following credo is meant to guide you in enhancing an already inclusive school culture to include students with complex needs.

Inclusion Outreach’s Credo for an Inclusive School Culture for Students with Complex Needs

- There is no prerequisite to inclusion

- All means all

- Every student has the right to be seen as a learner

- Always presume ability

- Provide what is needed

Case Examples

Lou Brown, a pioneer in inclusion for people with severe disabilities, is known for saying, “Pre means Never.” Pre-employment? Never employed. Pre-academic? Never learn. When practicing inclusion, there isn’t anything that must be accomplished or acquired or skills that must be learned first. Learning takes place in context. You cannot prepare someone to be included without including them. Prerequisites place responsibility on the student. Being included is not the student’s responsibility. Including all students is your responsibility.

Case Example: Isla

Isla is an elementary-age student. She is blind and ambulatory with assistance. The first thing we noticed as we approached her classroom was that her desk marked with her name tag was outside the classroom door in the hallway. A hook mounted on the wall beside the desk for her coat and backpack suggested this was not a temporary measure. It was clear that Isla did not have membership in her classroom. We were told that the reason she was not in the classroom was because she screamed, which disrupted the class. An additional space had been set up in an empty classroom at the opposite end of the school equipped with a ceiling-mounted swing and mats on the floor. This is where Isla and her EA spent most of the day every day.

Inclusion Outreach’s mandate is inclusion and we wanted to spend time with her in her classroom. It didn’t take long before we heard the reason she was excluded. Her scream was loud and piercing. When she screamed, she was taken to her room. After a while, another attempt would be made to join the class. Usually with the same result. Our observations in the classroom showed us that the screaming occurred when there were transitions in the classroom, and there were many throughout the day.

For example, the teacher would say, “OK class. Everybody line up to go to the library.” Isla screamed. “Carpet time for music.” Isla screamed. We had a copy of the class schedule that we used to anticipate when a transition was coming up. The SLP on our team sat next to Isla and calmly and quietly narrated to her the change that was to come.

“Isla, it is going to be time to go to the library soon. All the kids are going to put away their work, and they will be called to line up. Let’s put away your work and get ready for library.” Isla listened intently while she was told what was coming next. When her name was called to line up, she stood up. She was ready for library. This pattern repeated itself throughout the day. Isla’s EA used the technique with the same result. Before we left that day, we moved Isla’s desk and hook back into the classroom.

Not screaming was seen as a prerequisite to Isla’s membership in her class. Screaming had in fact become an adaptive strategy that Isla used to escape when situations in the classroom were too frightening or overwhelming. Helping her to manage transitions could not be taught in the classroom if she wasn’t in the classroom. There are no prerequisites for inclusion. Isla is not responsible for finding the solution. That is up to us.

For students with complex needs, simply being placed in a classroom with their peers is not inclusion. When we talk about all means all, we are talking about creating a sense of belonging where students with complex needs are fully participating and contributing members of their school community. Access must be available to all environments used by students in the school. Playgrounds and weight rooms are often found to be inaccessible to students with mobility issues. All floors and all environments must be accessible for all. All students belong in the classroom. Inclusion is about welcoming diversity in all forms: ethnic, racial, linguistic, gender identity, and ability. To be inclusive, the teacher must plan for the range of student ability in their class, not the class plus one.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is an approach that helps teachers design inclusive lessons from the start rather than retrofitting lessons to meet individual needs. A wealth of resources for UDL is available on the CAST (formerly Center for Applied Special Technology) website.

Check out Dan Habib’s award-winning documentary film, Including Samuel. The film chronicles the Habib family’s efforts to include son Samuel, who has Cerebral Palsy, in every facet of their lives.

Case Example: Grace

An elementary class was broken up into small groups to create a winter diorama. The teacher told the class that as a group they needed to come up with a process to make decisions about what ideas would be included in the project. Ideas like, “we could vote,” were generated, but it soon became clear that each member of the group was primarily interested in voting for their own ideas.

Grace is a student in the class with complex needs. She uses facial expressions and gestures to communicate and is learning to use a switch to control aspects of her environment like turning music on and off and participating in activities with her classmates. She is also learning to make choices. One switch operated device Grace is learning to use is a spinner. The spinner is a choice-making tool that is used in Grace's educational programming and recreational activities.

When Grace presses the switch, a tiny LED light races around the spinner and lands on a random point. Using the spinner Grace can participate in classroom activities that require a simple choice. The spinner comes with a set of overlays: a dice to play board games or participate in math activities—one with colours, and another that is blank and customizable with a dry erase marker. For instance, push ups, burpees, and jumping jacks could be written on an overlay, then Grace could use the spinner to select warm up activities in gym class.

For the diorama project, the group decided that choices would be made by playing, “Rock, Paper, Scissors.” We divided the overlay on the spinner into pie shaped sections and wrote Rock, Paper, Scissors in the spaces. A student would suggest their idea for the diorama, and then Grace touched the switch to determine whether their idea would be a winner. The activity was fun, and Grace was able to participate in a classroom activity while working on two of her IEP objectives—making choices and using a switch.

The teacher had designed a lesson in which all students were active participants and allowed for the range of ability in the class.

You need to believe before you can do. Henry Ford is quoted as saying, “Whether you think you can or you think you can’t, you’re right.” You need to believe that a student with multiple disabilities can learn and that you can teach them.

Case Example: Mia

Mia attends high school in a Lower Mainland school district and has a complex combination of physical, intellectual, sensory, and neurological disabilities. She has a seizure disorder that is of particular concern, and she requires close monitoring and administration of medications at home and at school. The combination of seizures and medications is very sedating, and Mia does sleep at school. The 1:1 EA who monitors Mia and meets her care needs reported that Mia sleeps all day at school.

The EA reads a novel to herself most of the day while remaining close to Mia in case of a seizure. The EA was doing her job as a caregiver and obviously cared for and about Mia very much. However, Mia was not seen as a learner. Mia’s IEP specified learning objectives including teaching her to make choices with her eyes and greeting others with a smile, but Mia couldn’t work on these objectives while she was asleep.

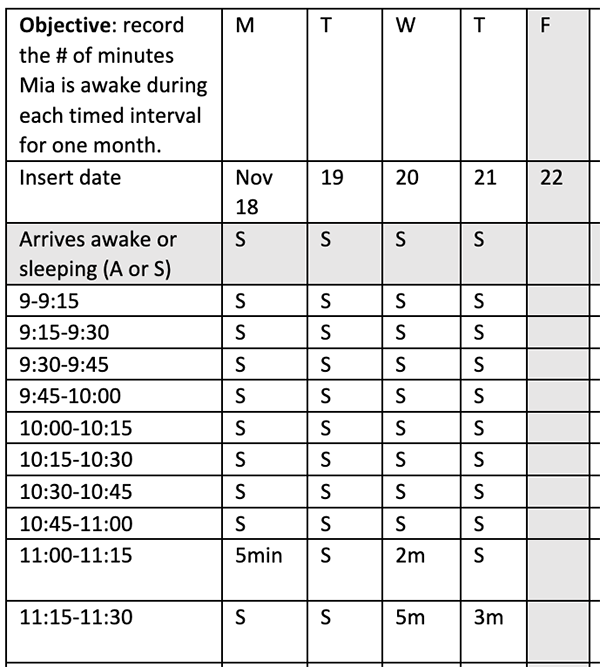

We suggested doing an instantaneous time sampling data collection to determine if, in fact, Mia slept all day at school. We divided the day into 15-minute intervals and over four consecutive weeks, the EA recorded at 15-minute intervals an “S” if Mia was sleeping or an “A” if she was awake.

What emerged from the data was that there was a consistent pattern when Mia was awake and alert from mid-morning, often until the end of the school day. We recommended that the EA be intentional during Mia’s wakeful time addressing her learning objectives during that time.

The EA was excited and “on board,” and her impression of Mia changed. Mia was now seen as a learner.

An example of Mia's data collection. Download the full chart (PDF).

All students learn differently. If you are the parent to more than one child, you already know that children learn differently. Take a strengths-based approach. Focus on what the student can do and build on those skills. Anne Donnellan, education professor at the University of Wisconsin, proposed that we follow the “criterion of the least dangerous assumption.” Educational decisions ought to be based on assumptions that would have the least damaging consequences. We need to assume students with complex needs are able to learn because to do otherwise would result in fewer opportunities provided, fewer choices offered, and a lesser quality of life (Jorgensen, 2005).

Case Example: Olivia

This story is about Olivia, a student we supported who attended a large elementary school. Olivia needs to spend about 45 minutes a day in a stander to stretch her muscles and bear weight through her legs. Olivia is learning to use a communication app on an iPad. The stander was on wheels and could go anywhere in the school. We asked her if she would like to go to the office in her stander and tell the principal a knock, knock joke. Her smiles and vocalizations clearly told everyone that this was something she was excited to do.

She was taken in her stander to the foyer in front of the office, and a message was sent to the principal to ask if he could come out and see her. Telling the joke required her to touch the screen on the iPad four times: 1. Do you want to hear a joke? 2. Knock, knock, 3. Ach, and 4. Bless you. The principal knew his lines, and the joke was told. Everyone laughed.

The Inclusion Outreach team had watched this interaction from a distance so as not to interfere. A teacher had been walking through the foyer and stopped to watch with us. She had seen Olivia at school but only knew her from a distance. At the end of the joke when everyone was celebrating Olivia’s success, the teacher said, “I didn’t know she was a thinking person.”

It was an important lesson in preconceived notions. Remember Henry Ford—we presumed Olivia could do it, and we were right. Wayne Gretzky reminds us how important it is to try: “You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.” You only succeed if you try.

Provide what is needed in order for the student to be successful. “Students learn best when they are valued, when people hold high expectations for them, and when they are taught and supported well” (Jorgensen, 2005). Students with complex needs will likely require significant supports to be successful contributing members of their classrooms and schools. They could also require accommodations to the curriculum or to the physical environment of their classroom. Most importantly, students with multiple disabilities need opportunities— opportunities to be engaged, opportunities to demonstrate their capacity, and opportunities to be involved.

Case Example: Olivia, continued

Let’s continue to think about Olivia and the story about her telling the joke. With planning and forethought, Olivia was set up to be successful. The knock, knock joke was selected with her, and she was asked if she thought it was funny—she did. She was asked who she would like to tell the joke to, and she chose the principal. Olivia is learning to use a voice output app on an iPad to initiate conversations with others. In advance of telling the joke, she practiced. The iPad was positioned to facilitate access and hand-under-hand support was given to assist Olivia to touch the button on the iPad at the right time.

The approach we need is to teach the skill in the context of natural environments with the supports in place to make the task successful. As Olivia becomes more skilled, we gradually withdraw the support, and she is able to perform more of the task independently.

Providing the necessary support helped Olivia to be successful and motivated her to learn more.