Module 3: Vision

The Visual Pathway

Visual impairment can result from insult or injury at any point along the visual pathway.

Light may be blocked or distorted while entering the eye and unable to reach the retina due to problems with the cornea, lens, or vitreous humor (fluid that fills the eye). Light may reach the retina, but the retina may be unable to convert some or all of it into electrical signals. Or, the retina can convert the light to electronic signals, but the optic nerve may be unable to properly transmit those signals to the visual areas of the brain.

Lastly, the visual information may reach the visual areas of the brain, but the brain may be unable to effectively process these electrical impulses into perceivable elements in the sensory environment.

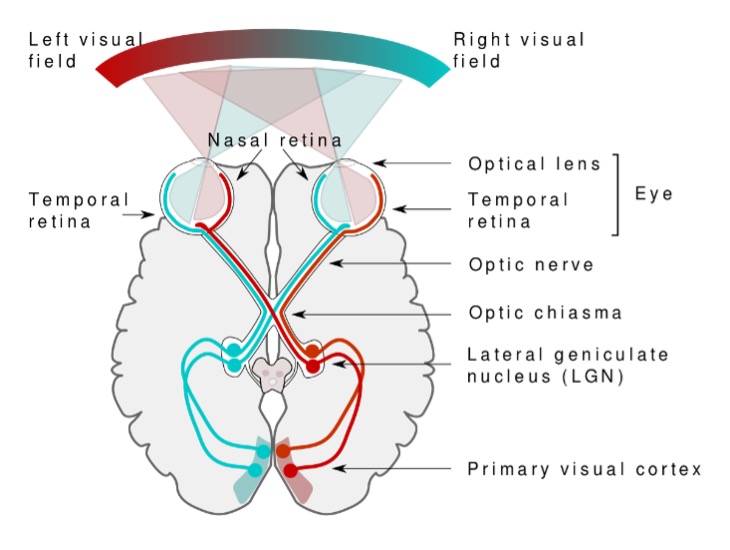

This diagram shows the brain’s visual system, including how information from the left and right visual fields are transmitted from the retina to the primary visual cortex.

Effects on Visual Functioning

Depending on the areas of the visual pathway that are interrupted, vision may be impaired in several different ways and involve one or more of these functions:

- Visual acuity

- Visual field

- Contrast sensitivity

- Light sensitivity

Visual Acuity

Overall visual acuity, or sharpness of vision, may be reduced such as:

- Small objects or objects at a distance may not be seen

- Objects may need to be held closer or enlarged

- Less detail may be seen even with close distance and enlargement (e.g., details in a picture or on an iPad)

Visual acuity is measured using a range of techniques. Behavioural techniques relying on recognition of increasing smaller/crowded optotypes (e.g., letters, numbers, symbols) are common. For students who cannot be tested with recognition tests, preferential looking acuity measurements may be conducted. These involve examining the student’s reaction to high contrast visual patterns and are based on the observation that the student will preferentially look at the patten image (such as alternating white and black stripes of increasingly narrow width) over a grey area with no image.

Visual acuity can also be estimated using direct measurements of the visual part of the brain’s electrical responses, via electrodes, to changes in black and white patterns presented on a computer screen. This method, while only available in medical settings, is particularly useful when a student’s visual acuity can’t be estimated using recognition or preferential looking techniques.

The following is an image of a common recognition acuity measurement tool, the Snellen chart. It features lines of single letters that are progressively smaller and closer together, starting with larger letters at the top.

Visual Field

The visual field is the area that can be seen in one glance without moving the head or eyes. With some visual conditions, areas of the visual field may be unavailable to the student.

Some students may appear to look off to one side so that they can use the area of visual field that is clearest to them, even if it is not straight ahead. This is called eccentric viewing.

Visual fields are estimated using a range of techniques. The most practical means of estimating visual fields is using confrontation visual field testing. The student is presented with a visual target, asked to fixate, while a second target is brought in from the periphery towards the fixation target. The evaluator observes the point at which the student’s gaze shifts from the original target to the peripheral target as a means of estimating the functional visual field. Other techniques for estimating visual fields involve more elaborate apparatuses typically found only in medical settings.

These images demonstrate the impact of a left homonymous hemianopia, where the visual field loss is in the same segment of the left visual field. The viewer would only reliably perceive what is in the right visual field with their eyes and head held steady.

Colour and Contrast

Some conditions affect colour perception or may reduce the ability to see low-contrast objects.

Contrast and colour can have a major impact on a student’s ability to see material. Therefore, when presenting material:

- Use high-contrast text or images

- Eliminate glare off pages or screens

- Ensure backgrounds aren’t busy or cluttered

High-contrast visual targets are easier for all students to see. Further, it is important to not use colour as the only means of distinguishing or labelling items in a visual display.

The tractor on the left is a low contrast visual target, while the barn on the right is a high-contrast target. The high-contrast white barn on the dark green background is much easier to see than the light green tractor.

Lighting and Glare

Some conditions mean functional vision is more effective in bright light conditions and less effective in low light. Other conditions may cause just the opposite effect with the best functional vision in dim lighting and reduced functional vision in bright lighting. Therefore, lighting needs will depend on a student’s specific visual condition and functional vision. A teacher of students with visual impairments will be able to provide specific information about lighting and glare accommodations for individual student needs.

Consider:

- Lighting may be too dim or too bright

- Light reflecting off surfaces may create glare

- Specific visual conditions may create excess glare (such as cataracts)