Module 3: Behaviour is Communication

Supportive Strategies

There are a variety of strategies you can use to support students in the classroom.

Asking a student is the best place to start when figuring out what a student is communicating through their behaviour.

Family, classmates, and school staff might help figuring out “what’s up” based on their knowledge of the student. Asking the student directly is respectful and includes them in the communication learning process.

Always confirm the student’s understanding by watching their facial expressions and body language. Repeat and rephrase your instructions, use different words, and see if you can determine their understanding. Work with your school SLP to assist with interpreting the student’s communication.

Language might need to be simplified or adjusted in what you say, or how you say it.

Use short simple sentences when speaking to students. Be careful not to leave out the little words and distort the normal intonation of what you say. Intonation is important to meaning.

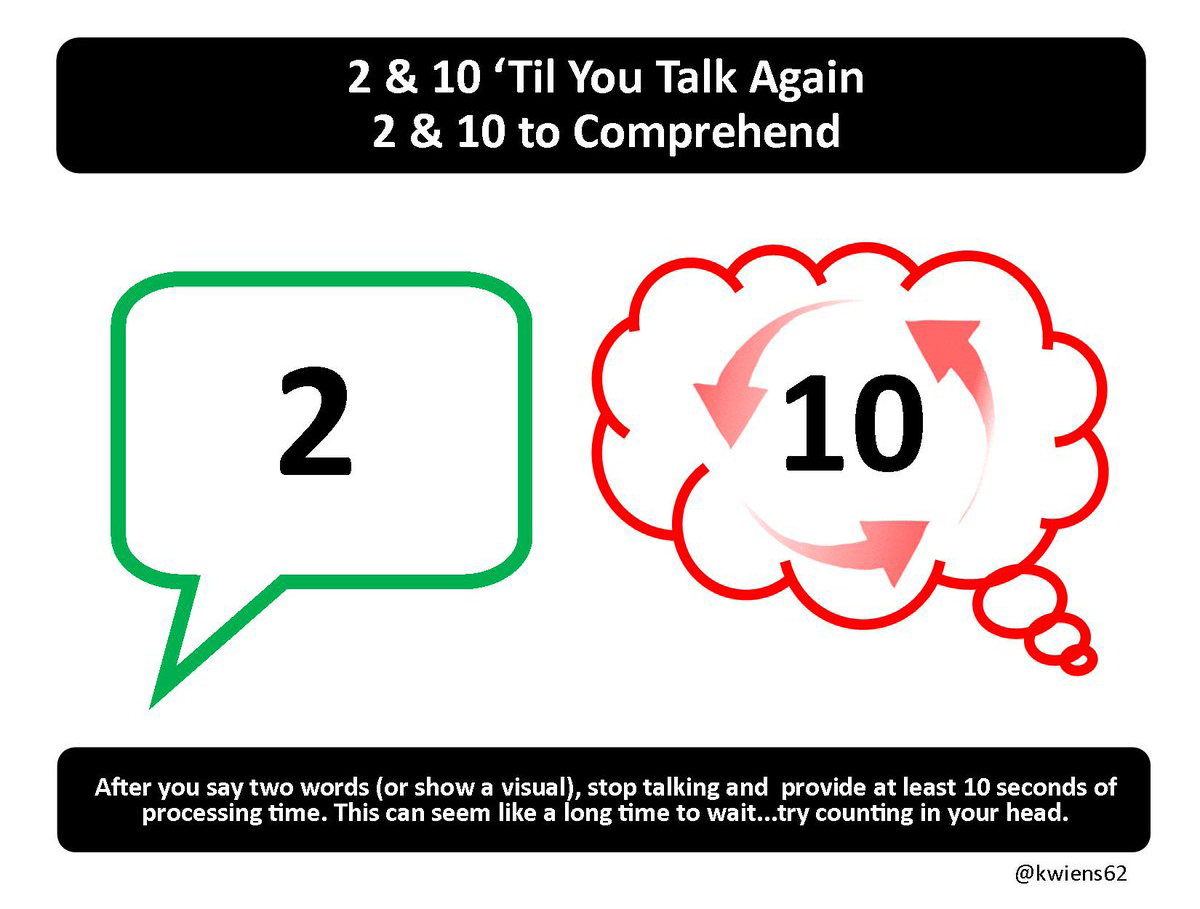

Waiting to give a student time to think about what you’ve said and respond is a very important part of this strategy. The amount of wait time needed will vary, depending on the student and their familiarity with what you are saying. Use respectful language when speaking to students and speak to them the same way that you would to any other student in their grade.

Consider adjusting what you say and how you say it to students with complex needs:

- Use short, simple phrases

- Use intonation to clarify what you are saying

- Speak as you would to any member of the class

- Wait for their response—give the student time to process what is being said

- Take a total communication approach (model, use AAC, pictures, symbols)

- Acknowledge gestures, vocalizations, and facial expressions

- Confirm with the student that your understanding is correct

Sometimes students will use language that we don’t understand or recognize the meaning of. For example, they may ‘script’ an entire scene from a movie or a line they have heard or read, etc.

For these Gestalt Language Processors, it is important to respond to the gestalt (sometimes called a ‘script’) as meaningful. It may be difficult to know the meaning of the gestalt because they are often not literal. In this case, repeating the gestalt back to them or saying ‘yeah’ or ‘uh huh’ lets them know you heard them and recognize their communication attempt.

If the meaning of the gestalt is known, providing the student with a model of more conventional language that represents what they are trying to say can be helpful.

Your school based SLP may be able to give you more information on gestalt language processing and strategies you can use.

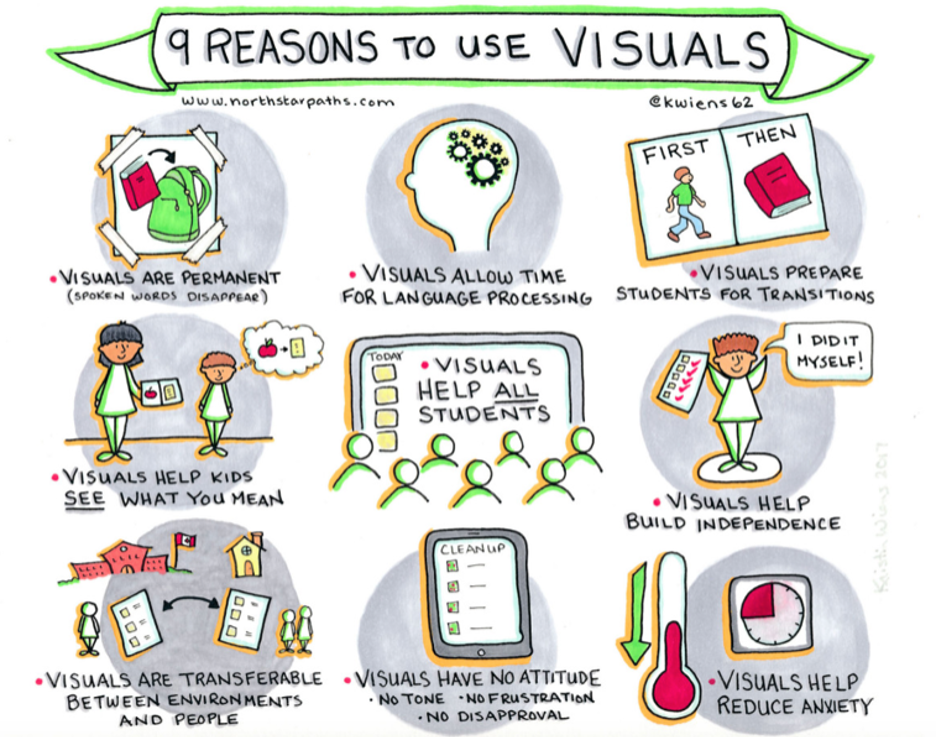

Visuals in the forms of photographs or symbols are often used to support a student’s understanding of a concept, what is being said, or the daily routine.

"6 feet apart" sign

"Entrance door" sign

Arrows on wall

The following graphic "9 Reasons to Use Visuals" was produced by Kristin Wiens. Kristin is an Inclusion Coach in School District 62 (Sooke).

Visuals may need to be modified. For example, they could be:

- Enlarged

- Photographs rather than line drawings

- Placed in a certain part of their visual field

- Placed against a black background

Your Teacher of the Visually Impaired may be able to suggest specific strategies for your student.

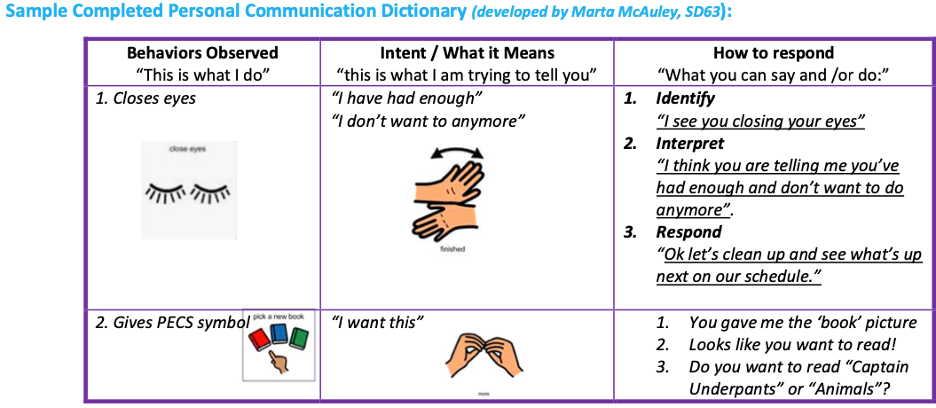

Students with complex needs benefit from a powerful tool known as a Personal Communication Dictionary (PCD). People who know the student well generally have a good understanding of what the student is trying to communicate and can anticipate their needs. A Personal Communication Dictionary is a tool that shares the knowledge of people who know the student well and gives a common understanding of what the student is saying.

The Personal Communication Dictionary allows educational teams to have a common understanding of and response to a student’s communication attempts. The more consistently people respond to a student’s attempts to communicate, the more likely they are to communicate!

PCDs are made by recording what a student does (their behaviour), what the team believes that behaviour means (intent), and how team members should respond. This ensures everyone is being consistent in the way they communicate with the student. Having a consistent response does not mean everyone has to say the exact same thing. Remain natural, emphasize key words, and speak respectfully to the student.

Personal Communication Dictionary

| Behaviours Observed | Intent/What It Means | How to Respond |

|---|---|---|

| "This is what I do" | "This is what I'm trying to tell you" | "What you can say and/or do" |

What the student is doing:

|

Our "best guess" interpretation of what the behaviour means, such as:

|

Use a three-pronged response format to communicate with the student:

|

| The document "How Do I Communicate" shows other examples of ways people can communicate | The document "Why We Communicate" gives some examples |

The “How Do I Communicate” and “Why We Communicate” documents are available on the Inclusion Outreach website.

When creating a Personal Communication Dictionary:

- Identify and clearly describe the student’s behaviour so that all members of the student’s team share a common understanding

- Interpret the behaviour (what you think the student’s behaviour means. Again, the team needs to arrive at a shared understanding)

- Decide on the appropriate response for team members to follow to ensure consistency

At Inclusion Outreach, we recommend that a three-step response be used:

- Tell the student what you see them doing

- Tell the student what you think they mean

- Respond to the student

Using this approach acknowledges that you are listening. It is important to model this approach so that others in the student’s environment understand how the student is communicating, what they are telling us, and how to respond in a consistent way to their communication.

All the ways a student communicates are reinforced with verbal language. The intent isn’t necessarily to replace behaviours with words. Talking to the student strengthens the connection between words and their behaviours.

Design classroom activities so that the reinforcement is intrinsic for all students. Intrinsic reinforcement means that the positive reward is embedded in the activity.

Case Example: Intrinsic Reinforcement

Here is what designing for intrinsic reinforcement could look like:

In the morning, the student is reminded to check their visual schedule (which is an effective support for their receptive language and executive functioning), to see what they are expected to do. It clearly indicates that they need to get the iPad from the charging station and check to see if it is working. Their role is to turn the iPad on, check the battery life, and open the communication app. These expectations are well within the student’s ability. The student has already mastered these skills.

The student then has a visual cue that clearly indicates that they are waiting for their turn to say how they feel, using the iPad app. The second visual also supports comprehension. Again, they are less anxious because they know what they are expected to do. Because they are less anxious, they are ready to engage. When it’s their turn, the student uses their communication app to share how they are feeling. The teacher records their words onto the whiteboard and helps the whole class read out the words. All the student’s classmates pay attention when they “talk” using the communication device, which intrinsically rewards the student, as they feel respected and included by their peers.

Choose learning objectives that target the student’s Zone of Proximal Development (that sweet spot where the student is stretching their learning, but what they’re learning is not too big of a stretch). In the Inclusive & Competency-Based IEP (I&CB IEP), skills that fall in this sweet spot are the ones you can include in the section called Stretches. The sweet spot is where the student is likely to experience success with support.

Let’s return to the case example about the student who was asked to check to see if the iPad was charged up and working. They were asked to do this part of the routine because they had already mastered this skill. Their new learning in the routine was to tell the class how they were feeling using the communication app on their iPad. This new learning was a stretch, but not too big of a stretch for the student. In other words, it was a skill that lay in their zone of proximal development.

Teach new skills one at a time to students with complex needs. Connect the new skill to a familiar environment or a previously mastered skill.

For example, when you teach a student a new skill, teach it in a familiar routine (context). Teach how to use the voice output app TapSpeak Button in the context of a routine the student is already familiar with, such as the school arrival routine. Everything else is the same, and the only new part is touching the iPad.

Teach a new classroom routine using visuals they understand and words and instructions that are familiar.

Continuing with the case of the student who is sharing how they are feeling using their iPad, (the new skill they are learning), everything they needed to do to get ready for the new activity was familiar, well scaffolded, and involved skills the student had previously mastered.

All students can experience fatigue during a school day especially when learning new skills. This is particularly true for students with complex needs who have a myriad of complex medical conditions (chronic pain, seizures, medications) that cause fatigue.

Flexibility is key. Adjusted expectations can be necessary from hour-to-hour, day-to-day, and year-to-year. Be prepared to step back expectations during those times when the student is tired, in pain, returning to school after a prolonged absence, or having more seizures.

Stepping back our expectations, doesn’t mean to stop teaching altogether. Instead, provide more scaffolding such as hand-under-hand assistance, shorter work sessions, more frequent breaks, and practicing familiar skills.

When to step back expectations:

- Know your student. Consider their history, medical complexities, and likes and dislikes. Use the student’s Personal Communication Dictionary to understand when flexibility is needed

- Communicate with the family. Let them know what you see at school and find out how things are going at home

Opportunity for Practice: Personal Communication Dictionary

- Reflect on a student you’re teaching or working with. What behaviours do they use to communicate? What do you think they are trying to tell you when they use those behaviours?

- Build a personal communication dictionary for your student:

- Identify and describe the student’s behaviour

- Interpret their behaviour (what you thought the student’s behaviour meant)

- Decide on the appropriate response for team members to follow to allow for more consistency

- Share the personal communication dictionary you develop with other members of the team supporting the student. Identify any behaviours where people’s interpretations differ. Discuss a consistent response that all members of the team will follow.