Deinstitutionalization

Horrific conditions in several large institutions where children and adults with disabilities lived were uncovered in the 1960s and 1970s. These conditions further fueled the disability rights movement and led to the demand that large scale institutions be closed.

In British Columbia, deinstitutionalization occurred in the 1980s and 1990s. The framework for the deinstitutionalization process was captured in these three major steps:

- Do not admit any new patients/residents into institutions

- Facilitate the moving of individuals in institutions to community settings. In general, the communities were selected based on where the person (often as a young child) originated from or where their parents or extended family currently lived

- Build community resources so that receiving communities were able to provide support to individuals returning

The closing of institutions, which had perpetuated the exclusion of individuals with disabilities was a good practice. However, many of the adults leaving institutions were returning to communities they had spent little or no time in and to families who may have been unable to maintain contact because of distance. Closing institutions accomplished the first two steps of the deinstitutionalization process. Questions remain about whether sufficient resources were allocated to develop services in communities to meet the need. The good intentions were often overshadowed by unsettling and fearful times for people with disabilities and their families.

As you explore the Deinstitutionalization timeline, reflect/journal on the following:

- In 2006, in a speech to the B.C. Union of Municipalities, then-B.C. premier Gordon Campbell referred to deinstitutionalization as a “failed experiment.” Do you agree or disagree? Why?

- Is there anything you would have changed regarding the framework for closing institutions?

- How could the process have been made less unsettling for individuals and families?

-

20th Century

-

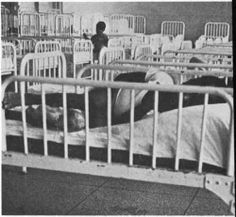

In the mid-1960s, Burton Blatt was a researcher in Connecticut investigating institutional care for people with disabilities. Blatt was horrified by the conditions he witnessed in institutional wards. He and photojournalist Fred Kaplan toured several large institutions and took photos with cameras concealed in Kaplan’s belt buckle. The photos were initially published in Look Magazine and raised public awareness about the conditions in these institutions. The photos were subsequently published as a photographic essay entitled Christmas in Purgatory. In the foreword to Christmas in Purgatory, Seymour Sarason writes:

“...the conditions...were not due to evil, incompetent or cruel people but rather to a concept of human potential and an attitude toward innovation which when applied to the mentally defective, result in a self-fulfilling prophesy. That is if one thinks that defective children are almost beyond help, one acts towards them in ways which then confirm one’s assumptions.”

Seymour Sarason, Christmas in Purgatory: A Photographic Essay on Mental Retardation (Foreword)

Christmas in Purgatory: A Photographic Essay on Mental Retardation

-

Conditions at Willowbrook, the largest institution in the United States for people with developmental disabilities, were described by Senator Robert F. Kennedy in 1965 as a “snake pit”. Exposés by Kennedy, and Blatt and Kaplan, were followed by Geraldo Rivera’s 1973 report entitled Willowbrook: The Last Great Disgrace. Scenes from Rivera’s report were aired on WABC-TV and viewed by millions.

Willowbrook, the institution that shocked a nation into changing its laws

-

The move to close large-scale institutions had its beginnings in the 1970s and gained momentum in the 1980s. The Ministry of Social Services and Housing, and the Ministry of Health’s Services to the Handicapped branch supported moving people out of institutions and into group homes in communities throughout the province. Attempts were made to move people back to their communities of origin to reunite them with family.

"During the 1970s and 80s, as we learned more about the untapped potential of people with developmental disabilities, the push to close large institutions gained momentum. Government services began to focus on providing supports to children, youth, and families in their local communities. This included a much greater effort to develop supports in public schools for students with special needs."

-

“The 324 patients still at the centre were transferred to community care, family homes, or other institutions. According to one article in the BCMHP News, there were 55 patients who were not considered able to return to the general population and were moved to Glendale, which brought about protests from families wanting to keep their loved ones close by.”

Jenna Wheeler, Kamloops News

The deep, dark and mysterious history of Tranquille Sanatorium and psychiatric institution

-

In 1996, Glendale Lodge was closed. Most of the residents were moved into group homes in the community. The site later became the Vancouver Island Technology Park.

-

In response to advocacy from families, the B.C. provincial government announced plans to close Woodlands in 1981. Fifteen years later, Woodlands finally closed. British Columbia was the first Canadian province to close large institutions for people with intellectual disabilities.

-

21st Century

-

Following the closure of Woodlands School, an independent review was conducted by B.C. Ombudsman Dulcie McCallum in response to allegations of abuse filed by former residents. The Need to Know report, released in 2002, revealed a culture of systemic abuse and a conspiracy of silence that perpetuated physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. The report recommended an apology and monetary compensation to survivors.

Institutions and People with Intellectual Disabilities